The Story of “Kyo-no-Koto,” the Trigger for the Birth of Kyoto Yeast

~Interview with Nobuo Tsutsui, a Retired Employee of KMIITC~

In July 1956, the Japanese government declared in its economic white paper, “Japan is no longer postwar”. In March 1966, at the height of Japan’s so-called period of rapid economic growth, the decision to invite Japan’s first World Exposition to be held in Osaka attracted public attention. The total population of Japan exceeded 100 million, and the country’s average annual economic growth rate reached 11.8%. In 1966, at the height of the economic boom, the Kyoto Municipal Industrial Experimental Station, precursor of KMIITC, was established in Minami Ward, Kyoto City, as a result of a merger of related organizations. In addition to providing technical guidance for Kyoto’s traditional industries, such as ceramics, lacquerware, and other traditional industries, as well as the machinery and metalworking industries, this public research institute also conducted tests, surveys, and provided technical guidance related to sake brewing.

Nobuo Tsutsui, a retired researcher who spent 40 years at the former Kyoto Municipal Industrial Experimental Station, remembers the atmosphere of this era. Mr. Tsutsui joined the Laboratory of Brewing, Kyoto Municipal Industrial Experimental Station, in November 1973. He spent six months of the brewing season (September to March) working on the yeast distribution and the remaining six months on brewing-related research.

At that time, the sake industry was still booming, and there were more than 50 breweries in Kyoto City. There were mainly two types of yeast: Koshi (Japanese abbreviation for Industrial Experimental Station) No. 1, which was based on Kyokai No. 6 yeast, and Koshi No. 2, which was based on No. 7 yeast. Mr. Tsutsui recalls, “At that time, we were busy for six months during the brewing season making yeast to be distributed to the breweries. The record shows that in its height, we sold 3 or 4,000 of 3-deciliter bottles containing the yeast in one month, or about 12,000 bottles in one year.”

At that time, it was considered ideal to make a large quantity of regular sake such as “josen” (top-grade sake) in a stable manner. “Both Koshi No. 1 and No. 2 were yeasts with stable fermentation power, and in that sense, they were easy to use,” Tsutsui recalls.

According to Tsutsui’s memory, the demand for yeast in Kyoto peaked in 1978, after which the environment surrounding the sake industry changed drastically. At the same time, the ginjo sake boom came along. Small and medium-sized sake breweries shifted their product lineups to premium sake with gorgeous aroma to survive. Kyoto’s sake breweries were no exception, and gradually the need from the breweries to researchers became apparent: “Can you share your aromatic yeast with us?”

Since 1989, Tsutsui has been involved in yeast-related work, and in 2005, he became the head of the research department. At first, he tried to meet the need for a yeast that would win a gold medal at the annual National New Sake Competition, but eventually felt uncomfortable about this. He wanted to create a yeast for ginjo sake that the public would enjoy drinking, so he isolated a new, as yet unnamed yeast called No. 221.

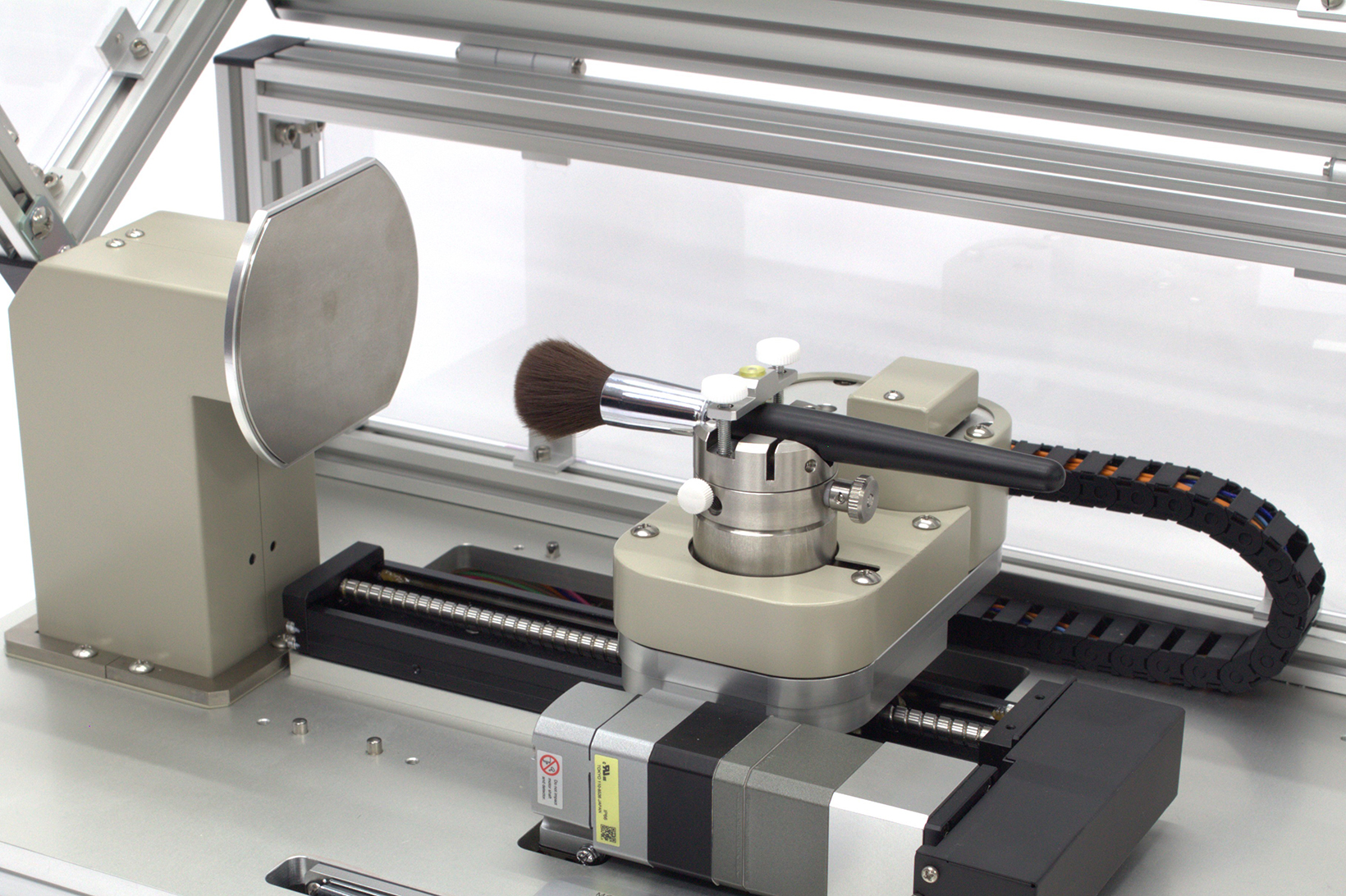

At the time, the Kyoto Municipal Industrial Experimental Station did not have a brewing license to conduct experimental brewing. Experiments showed that the yeast produced an aromatic yeast with a significantly high ethyl caproate value. However, without conducting a small test brewing, it was impossible to know whether it would contribute to practical use. If it failed, he would be putting the breweries at risk of failure.

Tsutsui hesitated, but he boldly asked the Sasaki Brewery in Kyoto City to conduct the test brewing. Katsuya Sasaki, the previous generational president of the brewery, readily agreed, saying, “It makes sense for a small brewery like ours to conduct a test brewing.” Tsutsui was relieved and at the same time elated that the new yeast he had isolated would actually be brewed into sake.

The test brewing at Sasaki Brewery was a success, and Tsutsui gave the yeast number 221 the name “Kyo-no-Koto”. The name “Kyo-no-Koto” contains the word “koto,” which means “a harp” in Japanese, and was chosen to express the idea that “just as a harp can play many different sounds, different breweries can make different types of sake.”

Tsutsui’s success was crowned by the development of an excellent yeast called “Kyo-no-Koto”. He said, “Above all, I was able to create something that everyone enjoyed. This is something I can be proud of being a civil servant”. Tsutsui’s passion and achievements are being passed on to his successors.