The Discovery of Yeast

Tracing the History

For those who love to drink, after a day’s work, for example, an alcoholic beverage sipped in the evening with a group of close friends or family members brings an irreplaceable sense of fulfillment.

Needless to say, one of the most important chemical reactions in human civilization is combustion, or usage of fire. It is not an exaggeration to say that fermentation is perhaps the next most essential chemical reaction for the human race. Ancient civilizations around the world have discovered their own methods of making alcohol, and only the Arctic and some indigenous Australian ethnic groups did not discover fermentation on their own.

The first human civilization is said to have been the Sumerian civilization in Mesopotamia, where beer was already being made. It may be too much an exaggeration to say that humans gave up nomadism and settled down in order to make beer and created agriculture as a means of sustainable grain production, but still it is true that making alcohol is an activity that is deeply engraved in the DNA of Homo Sapiens.

To produce alcohol, a substance that brings pleasure to the brain, we are compelled to borrow the power of fermentation. At this point, yeast is at work, eating single sugar and emitting alcohol. Over the years, we humans have unknowingly domesticated certain wild yeast for producing alcohol, just as we have domesticated cattle.

For thousands of years, however, people did not know that it was microorganisms that were responsible for fermentation. 2,500 years ago, the Greek philosopher Aristotle hypothesized that a liquid containing sugar, when left to stand for a while, would turn into alcohol because of “vis viva,” the life force that drives all living things toward their goal. In other words, he believed that grape juice became wine because grape juice had a sense of purpose to become wine and exerted its own life force. On the other hand, the “Beishan Sake Sutra,” a book on sake brewing written in the Song dynasty (1117) in China, describes a process called “dry fermentation” in which the dried foam of the mash is added to new mash to stabilize the fermentation process. In other words, the Chinese of the time knew that adding the foam from the mash to new mash would produce sake, and that drying the foam would preserve it. In any case, however, they were not aware of any microorganism called “yeast” at work.

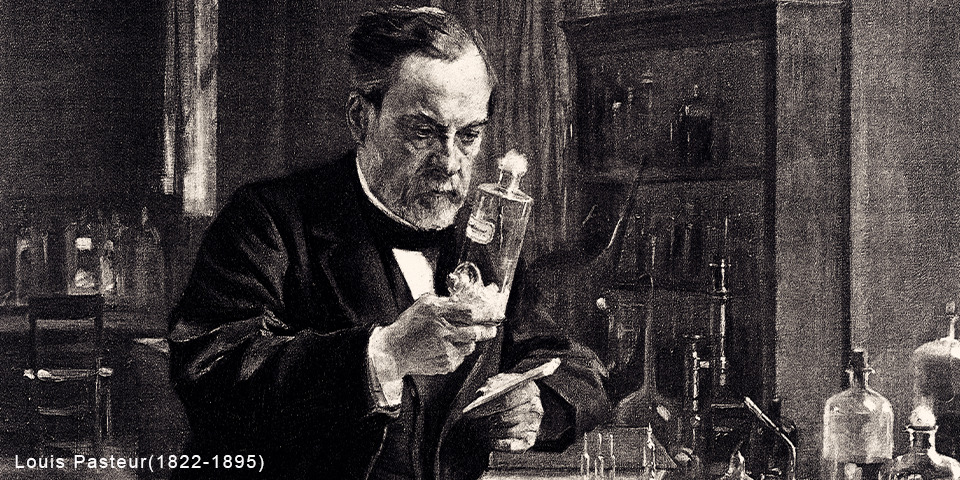

It was Anton van Leeuwenhoek of the Netherlands in the 17th century who first discovered that a microorganism called “yeast” was involved in the role of fermentation, but no one at the time could understand the significance of his epoch-making discovery. Another 150 years later, in 1837, German physiologist Theodor Schwan proposed that the microorganism discovered by Leeuwenhoek was responsible for fermentation. This microorganism was named Zuckerpilz (sugar fungus) and gave rise to the later Latin name Saccharomyces. In 1858, the French researcher Louis Pasteur finally proved that fermentation is the work of microorganisms. This marked the beginning of research on fermentation and yeast.

In Japan, research on yeast began during the Meiji period (1868-1912). Robert Atkinson, a British researcher invited from England, wrote “The Chemistry of Sake Brewing” in 1881, which was a pioneering work on sake yeast in Japan. In 1895, the first sake yeast was isolated by Kikuji Yabe, and it was named Saccharomyces sake Yabe in 1897. The modernization of sake brewing was in line with the Meiji government’s desire for more effective taxation. If the quality of the sake improved, consumers would buy more sake, thus increasing the amount of taxes the government collected. In this light, research on yeast and sake brewing began to flourish.

Before the Meiji era, sake brewing relied on ambient yeast that lived in the brewery. This resulted in inconsistent strains of yeast making the quality of sake unstable. In 1904, the Meiji government established the National Brewers Institute (now the National Research Institute of Brewing/NRIB) under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance, which introduced microbiology from the West, isolated useful yeast strains, and distributed them to sake breweries. In 1906, an association was established to contribute to Japanese society with the research results of the National Brewers Institute, and it eventually became the Brewing Society of Japan. The earliest yeasts isolated and bred by the Brewers Institute were Kyokai (Japanese word meaning “association”) No. 1, isolated from Sakura Masamune in Nada, Hyogo prefecture and Kyokai No. 2, from Gekkeikan in Fushimi, Kyoto prefecture.

Sake yeasts currently used in the sake industry include those distributed by the Brewing Society of Japan and local government R&D facilities, as well as those isolated and cultivated independently by universities and individual breweries. Sake yeast strains that have adapted to the sake brewing environment have been selected over the long history of sake, and the yeasts that have been considered industrial standards, such as Kyokai No. 7 and No. 9, can be considered elite that has survived numerous selection and testing processes.

The accumulated efforts of microbiological researchers since the Meiji era (1868-1912) have been the source of beautiful sake. As yeast has the name meaning “mother of fermentation” in Japanese, it has brought joy to human beings. It would not be an exaggeration to say that sake yeasts are true gems created by the tireless efforts of researchers and people in the sake industry.