History of Sake in Kyoto and Fushimi District

~The Checkered History from Ancient Times to Present~

Nowhere other than Kyoto can claim that the history of Japan is almost identical to the history of its own. The very name “Kyoto” itself means “capital city”. In the world of sake, Kyoto Prefecture is currently one of the nation’s leading brewing centers, with 41 sake breweries, mainly in Fushimi (Source: Kyoto Pref. Federation of Sake Brewers Associations website, as of November 5, 2022). Matsuo Taisha Shrine, revered by sake brewers nationwide where the “Deity of Sake” is enshrined, is also located here in Kyoto.

However, it does not appear that sake was first made in Kyoto. It is certain that people in the Japanese Archipelago began to make sake from rice at least as soon as rice cultivation methods were introduced from the continent and rice could be harvested stably. However, we still do not know exactly when this started, nor do we know where it originated.

The earliest record of the existence of sake in the country of Japan is found in the Section of Wa people, Wei Chapter, “Sanguozhi (The Records of Three Kingdoms)” written in the 3rd century AD in China. In this book, the Japanese are described as having “enjoyed some sort of alcoholic beverage” and it is said that mourners had a custom of “singing, dancing, and drinking” at the time of mourning. However, we do not know what exactly this alcoholic beverage was made from or how it was brewed. We have to wait until about 500 years after the time of the “Sanguozhi” for the Japanese themselves to write about “sake” made by saccharifying rice starch using koji, as is done today.

In the “Harima-no-kuni Fudoki (The Topography of Harima Province)” written in the early 8th century (around 716 AD), there is a description that “dried rice, which was a portable food, became moldy when wet, so they made sake from it and held a banquet with the sake.” Less than half a century later,” Manyoshu”, a collection of poetry compiled from 759 AD onward, contains a variety of poems about sake, so it is likely that by this time sake had become widely established. Ancient sake was usually highly viscous, as in the case of “nerizake”, which still exists in Izumo, Shimane Prefecture and Hakata, Fukuoka Prefecture.

The Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters) mentions that Susukori, a man from Baekje (Korean peninsula) brewed Omiki (sacred sake) and presented it to the emperor. The brewing method used by the Baekjeans probably involved the use of koji mold for rice saccharification before fermentation. From this time on, the brewing and drinking of sake during religious ceremonies came to be regarded as an activity of the Imperial Court, and in 689 AD, “Miki no Tsukasa (Office in Charge of Making Sake )” was established in Heijo-kyo (currently Nara) under the Asuka Kiyomigahara Ordinance, which was further systematized by the Taiho Ritsuryo Ordinance of 701 AD, which established a “system for brewing sake by the Imperial Court for the Imperial Court”.

In 794 AD, the capital was transferred to Heian-kyo (current Kyoto), and Kyoto became the political and economic center of Japan for the next thousand years. 868 AD, the “Ryo-no-Shuge” (Commentaries on the Civil Statutes) states that Heian-kyo had its own sake brewing department, Miki no Tsukasa, as did Heijo-kyo. According to the Engishiki, written in 967, the quality of sake at this time was a rich, mellow brew made by dividing the rice and koji into several batches.

During the Kamakura period (1185-1333), when commerce flourished in Kyoto, sake was distributed as a commodity with the same economic value as rice. In Kyoto, sake breweries, which both produced and sold sake, flourished. This trend continued during the Muromachi period (1333-1573), and by 1425 the number of sake breweries in Kyoto reached 342. The Muromachi period was a period of rapid growth for the sake brewing industry in Kyoto. At this time, a sake brand called “Yanagi” was famous throughout the country as “the best sake in Japan.” Today, Masuda Tokubee Brewery in Fushimi is selling the sake under the name “Tsukitsukatsura Junmai Ginjo Yanagi” in memory of this famous sake.

After the upheavals of the Warring States period, the Edo period came. Sake breweries, which were a lucrative business in the capital, were eventually established throughout Japan, and sake made in various regions began to be sold in the Kyoto market. Sake in Kyoto, which had prospered during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), suffered blows from repeated wars and large fires, and gradually declined as it lost out to competition from emerging breweries from Itami, Ikeda, and Nada. Kyoto’s sake breweries were wary of sake from other regions entering the city, calling it “yosozake,” and were eager to eliminate it. Shops in and around Kyoto often submitted petitions to the Edo shogunate’s magistrate’s office to stop the sale of inexpensive sake from other places.

From a bird’s eye view, this “sake from districts other than Kyoto” was the starting point of the local sake culture that would later support the Japanese sake culture. In the early Edo period (1603-1867), cheap and high-quality Omi sake was the rival. In the 19th century, Itami sake, which had lost out to Nada sake in the major consumption center of Edo (Tokyo), began to flow into the Kyoto market in large quantities thanks to the support of the Konoe family, a noble family that had Itami as its territory, putting a damper on the already struggling Kyoto and Fushimi sake. In Fushimi, the number of liquor stores in Fushimi was reduced from 83 in 1657 to 28 in 1785.

When the Edo period ended after the upheaval of the Boshin War and the Meiji era began, both Kyoto and Fushimi had been devastated by the great fire triggered by the Battle of Toba-Fushimi. There was one person who made a great contribution to reversing this overwhelmingly adverse situation.

The 11th head of his brewery, Tsunekichi Okura, expanded the size of the brewery operations by acquiring the former residence of a feudal lord and a disused brewery, and then modernized the brewery. The company also adopted an innovative brand name for the time, “Gekkeikan,” after the crown of a laurel tree given to the winner of the Olympic Games. This brand name eventually became the name of the brewery. In 1907, he introduced science and technology into sake brewing, and in 1909, he established the Okura Sake Brewing Research Institute as a corporate research institute.

At that time, sake quality was unstable and spoilage occurred frequently. Containers were transported in barrels and sold by weight at liquor stores. To prevent spoilage, the preservative salicylic acid was added to the sake. To solve this problem, the Okura Sake Brewing Research Institute scientifically established the conditions for heat sterilization and commercialized Japan’s first “preservative-free sake in bottles” in 1911. The “preservative-free” sake in bottles was strongly supported by the hygiene-conscious urban businessmen of the time, and Gekkeikan became well-known throughout Japan as an excellent sake. Furthermore, by skillfully utilizing the railroad network that was being developed at the time, Gekkeikan was able to expand into Tokyo, which had not been possible during the Edo period.

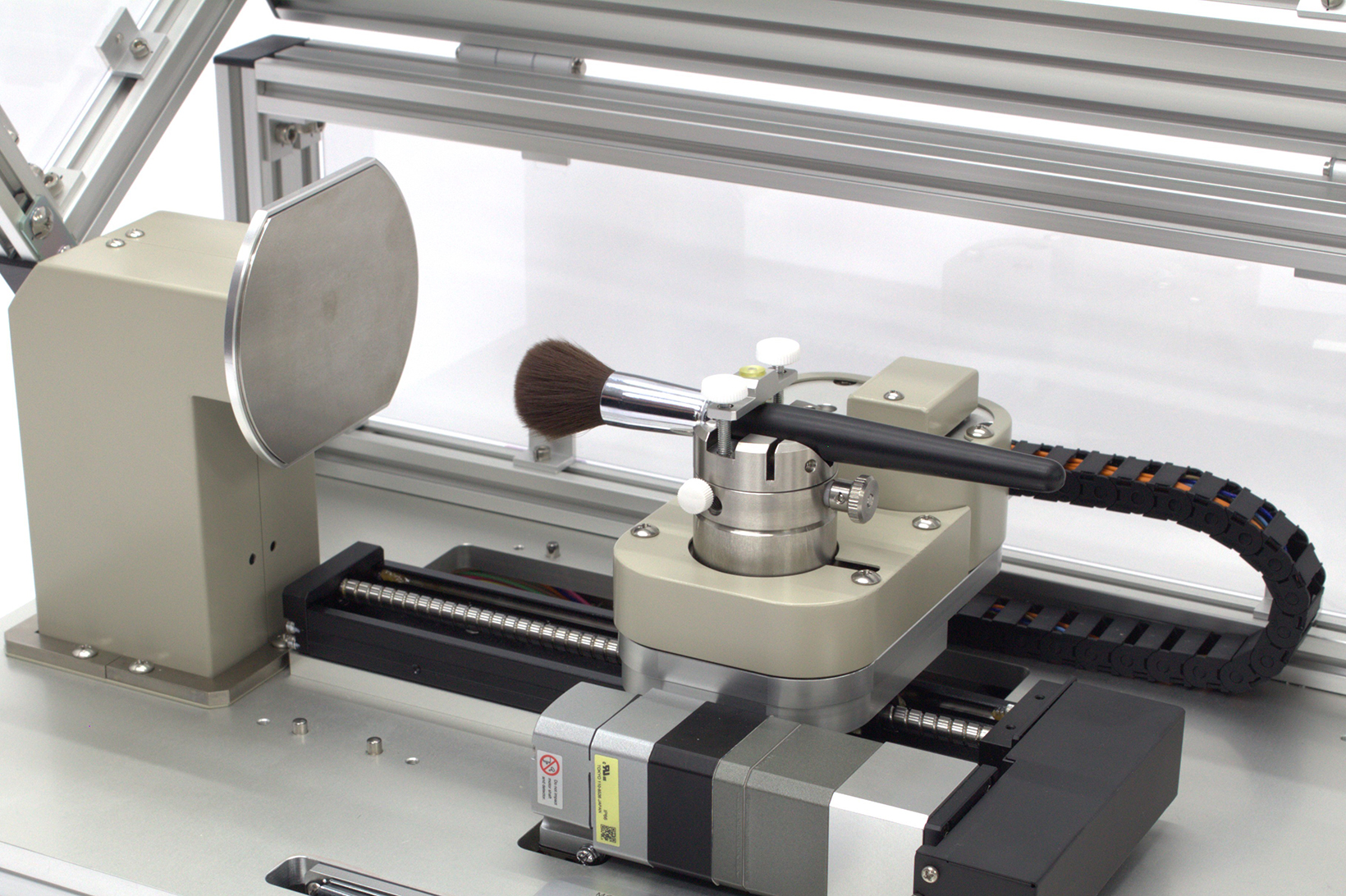

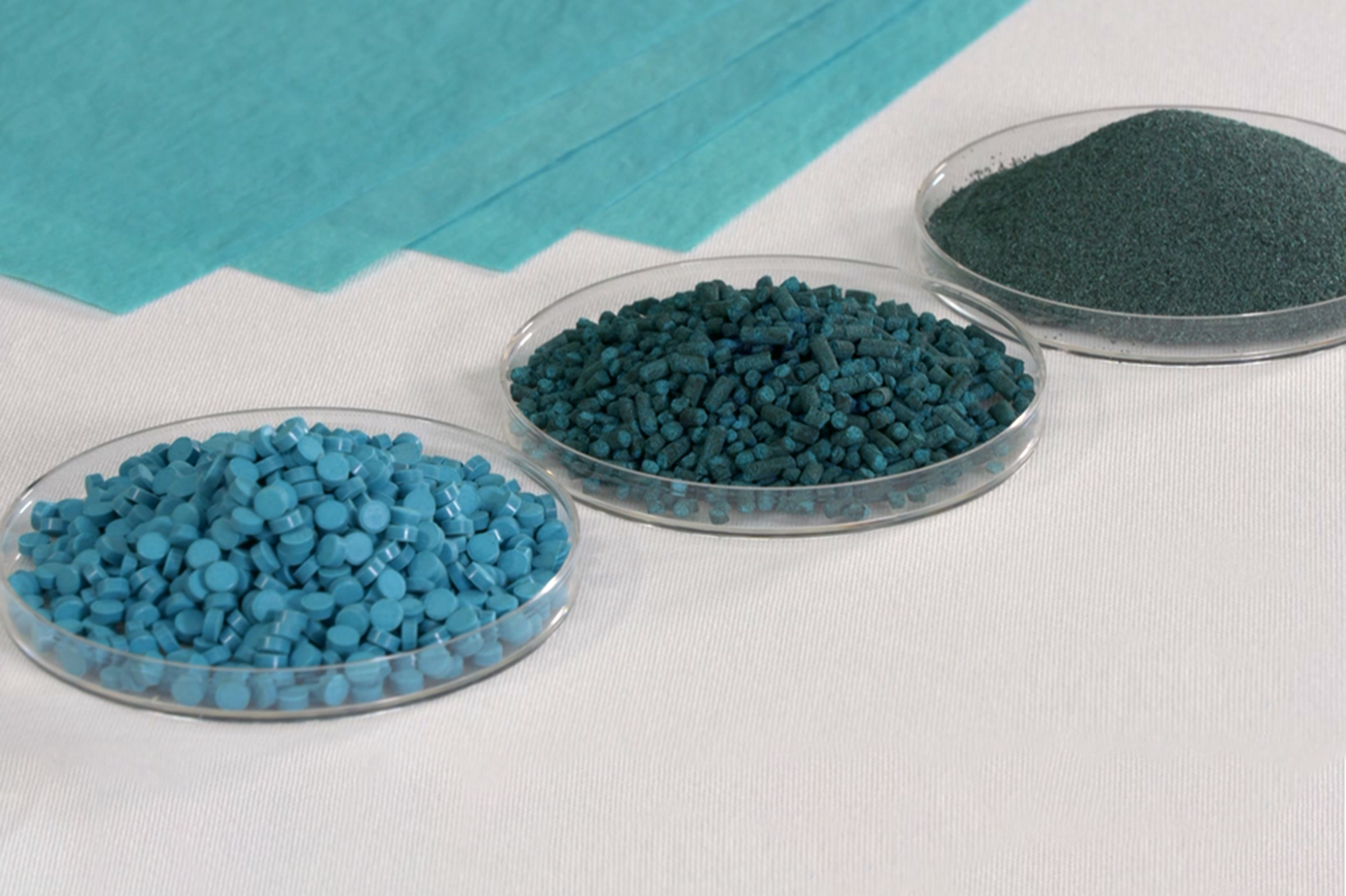

The reforms led by Tsunekichi Okura led to Fushimi’s prosperity as a center of sake brewing. These new initiatives were supported by the Fushimi Sake Brewers’ Association, which was formed in 1913. The Fushimi Joyu-kai (a fraternal association of sake brewers in Fushimi) was founded in 1913 with six members, and currently has 15 breweries as members. The Fushimi Joyu-kai introduced science to sake brewing, which had previously relied on experience and intuition, and supported Fushimi’s sake brewing in many ways;including the introduction of seasonal brewing equipment, the development of ginjo yeast and new brewing methods, and the development of raw rice and koji molds.

Today, Kyoto Prefecture holds the second largest position in sake production in Japan, after Hyogo Prefecture. Overcoming the hardships experienced during the Edo period (1603-1867), sake from Kyoto and Fushimi has blossomed into a magnificent flower.